The Fourth Protection: Loving-kindness

To say that loving-kindness is an important teaching in Buddhism is a monumental understatement. It is one of the things that Buddhism is most famous for. Loving-kindness is, of course, a million miles from what most people mean by love – the latter being sullied by attachment and possessiveness and often tainted with lust. Loving-kindness, on the other hand, knows no attachment. It knows no discrimination. And, when perfected, it cannot be undermined by another’s word or action – no matter how abusive. Loving-kindness is therefore a powerful and fearless state of mind; it is no pushover. It is not, as Ajahn Chah said while pulling a soppy face and rolling his head from side to side, all “Icky, icky, icky,” but it is capable of administering the bitter medicine. Most importantly, loving-kindness is steeped in wisdom. Without wisdom there can be no loving-kindness. The benefits of possessing a mind resplendent with loving kindness are, it goes without saying, innumerable, and its position among the Four Protections needs little explanation.

Hatred

Before we contemplate loving-kindness we should spend a moment considering the dangers of anger and hatred. Experiencing hatred is the mental equivalent of swallowing a red-hot iron ball. It burns, it is painful, it is destructive. Blood pressure rises, the heartbeat quickens, the face contorts, the stomach tightens. And if we allow it even an inch it will take a mile and we find ourselves rapidly metamorphosing into a demon, lashing out with our words and fists. How many times has a person got into an argument with somebody when a hammer was a little too close to hand? And then forty strikes and one smashed skull later he’s sitting in a cell that stinks of urine contemplating a life-sentence. Hatred kills our own happiness. It kills the happiness of others. It kills.

Which is why I found myself somewhat shocked the other day after coming across an interview between a devout American Christian and the well known and controversial atheist Christopher Hitchens. Ignorant of the extent of Hitchens’ materialistic views I was looking forward to a juicy and intelligent bit of creationism dismantling. Unfortunately I didn’t get it. (It might have come later in the interview but I didn’t stay around to find out.) Fairly soon into the conversation he launched into a vitriolic attack on the injunction to ‘love your enemy’. Not only did he strongly disagree with this sentiment, insinuating its immorality, but he said that we should actively hate the enemy. I was alarmed. How can an intelligent man think this? Well, intelligence is not the same as wisdom, and the latter is what Mr Hitchens clearly lacks in this respect. If he wants to make the world a better place he’s on the wrong track.

“Hatred does not cease though hatred, only through not hating does hatred cease. This is an an eternal law.” Dhp.

Thus as we remind ourselves of the destructive nature of anger and hatred our mind turns away from them as a hair recoils from a flame. We then reach towards the soft, warm, and healing light of loving-kindness.

Loving-kindness is steeped in wisdom

Ajahn Chah’s loving-kindness was legendary. Luckily, we are the inheritors of a vast fund of stories that testify to this… There was once an English monk staying at Wat Pah Pong who had been teaching English in Thailand prior to ordaining. After having been in robes for some time he received a letter notifying him of the tax he owed on the money he had earned while teaching. Not knowing what to do he mentioned his situation to various people in the monastery and their reactions were as you might expect: they moaned and grumbled and fobbed the tax collectors off. Then he went to Ajahn Chah to see what he thought. I doubt the monk was expecting this classic response: “You must help them,” said Ajahn Chah. “They have a job to do. You must help them.”

So his loving-kindness was all-encompassing. But how often do we read about Ajahn Chah actually teaching us to develop it? I cannot think of many instances at all. What we do find him constantly teaching, however, is the need to cultivate wisdom. This is because loving-kindness depends on wisdom. Without wisdom there can be no real love. Our loving-kindness will only go as deep as our wisdom, no deeper. And what is wisdom? It is insight into the Noble Truth of Suffering.

Some people feel that the term suffering is a little strong as a definition of dukkha. It’s true, we may want to refrain from using it too much when we introduce Buddhism to newcomers. But when we really begin to look at life, when we really see what life actually is, then we find that suffering is a pretty accurate description! We are born, we age, we get sick and we die. We balance precariously on the crest of the wave of impermanence, where every experience rushes by never to be seen again. We cannot hold onto any possession or person no matter how dear, for they are also swept away by this inexorable law of change. And at any time our life or the life of one close to us can be lost in an instant. How often do we see in the news a story about a family who were on their way to the seaside but never arrived? Did they ever think that could happen to them? Do we think that could ever happen to us? On seeing how all beings are oppressed by this same suffering loving-kindness wells up in us and we cannot help but think “May all beings be happy and free from suffering!”

And because loving-kindness sees that we are all of the same kind: vulnerable beings caught in the whirlpool of ignorance, craving, hatred and suffering, it is unconditional. It does not pick and choose. It does not think ‘I will love this person but not that person’. Just as the sun shares its light and warmth with all beings irrespective of race, religion, sex, gender or class, so too loving-kindness shares its warmth and light with all.

Non-Attachment

Seeing that genuine loving-kindness arises from wisdom, it must therefore be free of attachment. Attachment is a bar to real love. Some people new to Buddhism jump up and down when they hear this. Not long after I went to the monastery a woman whom I had known previously came to meditate with her friend. During tea-time she asked Luangpor this question: “Isn’t it irresponsible to not be attached?” This old chestnut arises because of a lack of understanding of what we mean by non-attachment, as if it is cold, heartless and uncaring. I’ll give an example that involves my mother to show how this isn’t the case.

Naturally she had a hard time accepting my move to the monastery nine years ago. At one point she went as far as saying that I might as well have been dead! But gradually the tables turned and she began to venture here on the odd occasion when I was giving a talk. “Tell me when you’re on,” she’d say. I suspect her interest was not initially in the Dhamma: I don’t imagine she heard a word I said since she was too busy watching me! But her eyes soon closed and the teachings settled in. That, combined with the meditation, inevitably meant changes took place. Then, last November, soon after my brother had left for Australia to find work, she unexpectedly discovered one of those changes when she saw how relaxed and cool she was on his departure. She was not overwhelmed by emotion. She didn’t wallow in a flood of self-pity. In other words, her selfish attachment had been reduced, and with it her suffering.

Can we say this was an uncaring reaction? Can we say it was cold? Of course not, because it wasn’t. It was a wise and sensible reaction that benefitted both herself and her son. After she had told me this we discussed the nature of attachment and how stupid and selfish it is. It is founded on what I want, what I need, how I want to feel, what I want you to do. Attachment is a bar to real love because it centres on ‘me’ and ‘mine’. Loving-kindness in the ultimate sense is blissfully devoid of all notions of self and other.

Under all Circumstances

Are there any circumstances when loving-kindness is to be exchanged for anger and hate? No. The Buddha went as far as to say that even if bandits were to sever you limb from limb with a two handled saw you should maintain a mind of compassion, and that whoever gave rise to a mind of hate would not be following his teaching. This is obviously a tall order: most of us might be slightly put out if we found ourselves in that position! But at least we know where Buddhism stands in terms of retaliation, violence and, especially, WAR. At least we know where to aim in even the most difficult circumstances.

There is a wonderful story of the Chinese Master Hsu Yun showing loving-kindness and compassion even in the face of the most brutal of attacks. He was in his 113th year when his monastery was besieged by a gang of hooligans. Monks were beaten and even murdered as the monastery was raided for money and weapons that the assailants believed were stored there. The master himself was dragged by a group of thugs to a small room and interrogated as to the whereabouts of the booty. But as their accusations were baseless he could only say that there was nothing for them to have. Determined to extract a confession the men pummelled him with their heavy boots and steel poles. As the blows rained down and the old master’s body crumpled to the floor he entered samadhi to escape the pain and to preserve his life. Thinking the master was dead, the group left him sprawled on the floor. His attendants then rushed in, and, detecting warmth in the cheeks of his battered face, sat him up in meditation posture before quickly departing. On returning the following day the thugs were furious to see him sitting up and so the boots and poles began to fly once more. When they came on the third day and found him again sitting in meditation they became frightened and fled. A week or so after the first attack the attendant monks heard the master groan. He had emerged from his state of samadhi only to become conscious of his pain-racked mangled body. Later on he was asked why he had come back, why he had not just renounced his life and attained Final Nibbana. His motives were loving-kindness and compassion: he couldn’t allow himself to die for it is a terrible karma to kill an enlightened being.

War

And war. Does it really need to be said that Buddhism does not condone war? Apparently, yes. Okay, soooo…. the case for a just war. On your marks. Get set….

A Buddhist country is under attack.

The very existence of the beacon of wisdom and peace hangs by a thread.

Aware that Buddhism will be destroyed if they do not fight the persecutors, the Buddhists take up weapons.

The enemy is thus destroyed and Buddhism saved.

Or was it?

NO. Of course it wasn’t. It was destroyed along with the enemy.

To die with loving-kindness in mind is better than living with blood on your hands.

To say that loving-kindness is an important teaching in Buddhism is a monumental understatement. Without loving-kindness Buddhism would not exist. Loving-kindness is, of course, a million miles from what most people call love; the latter being possessive, wrapped up with attachment, and often sullied by lust. Loving-kindness, on the other hand, is free of all attachment. It does not discriminate. It is not undermined by any word or action – no matter how abusive. It is not, as Ajahn Chah said while pulling a soppy face and rolling his head from side to side, all “Kutchi, kutchi, kutchi,” but is capable of administering the bitter medicine. It is therefore strong, fearless and, most importantly, steeped in wisdom. Indeed, without wisdom there can be no loving-kindness. The benefits of possessing a mind resplendent with loving kindness are, it goes without saying, innumerable, and its position among the Four Protections needs little explanation.

Hatred

Before we contemplate loving-kindness we should spend a moment considering the dangers of anger and hatred. Experiencing hatred is the mental equivalent of swallowing a red-hot iron ball. It burns, it is painful, it is destructive. Blood pressure rises, the heartbeat quickens, the face contorts, the stomach tightens. And if we allow it even an inch it will take a mile and we find ourselves rapidly metamorphosing into a demon, lashing out with our words and fists. How many times has a person got into an argument with somebody when a hammer was a little too close to hand? And then forty strikes and one smashed skull later he’s sitting in a cell contemplating a life-sentence. Hatred kills our own happiness. It kills the happiness of others. It kills.

Which is why I found myself somewhat shocked the other day after coming across an interview between a devout American Christian and the well known and controversial atheist Christopher Hitchens. Ignorant of the extent of Hitchens’ materialistic views I was looking forward to a juicy and intelligent bit of creationism dismantling. Unfortunately I didn’t get it. (It might have come later in the interview but I didn’t stay around to find out.) Hardly had the conversation begun when he launched into a vitriolic attack on the injunction to ‘love your enemy’. Not only did he strongly disagree with this sentiment, insinuating its immorality, but he said that we should actively hate the enemy. I was alarmed. How can an intelligent man think this? Well, intelligence is not the same as wisdom, and the latter is what Mr Hitchens clearly lacks in this respect. If he wants to make the world a better place he’s on the wrong track.

“Hatred does not cease though hatred, only through not hating does hatred cease. This is an an eternal law.” Dhp.1.5

Thus as we remind ourselves of the destructive nature of anger and hatred our mind turns away from them as a hair recoils from a flame. We then reach towards the soft, warm, and healing light of loving-kindness.

Loving-kindness is Steeped in Wisdom

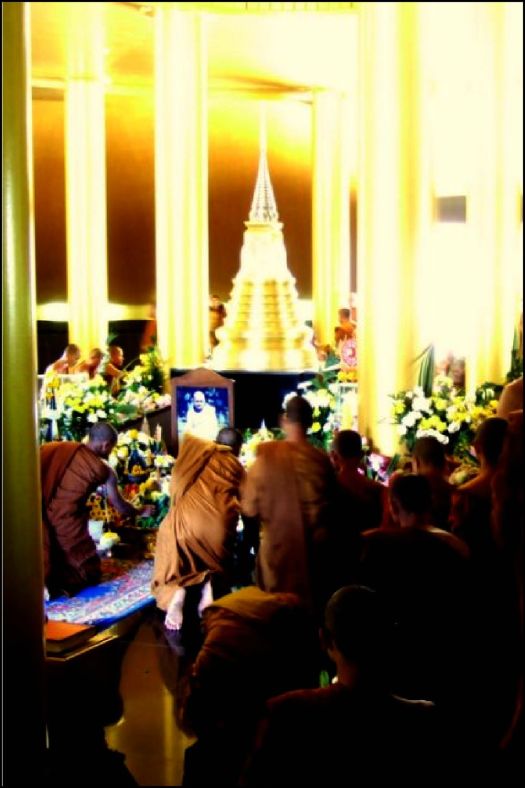

Ajahn Chah’s loving-kindness was legendary. Luckily, we are the inheritors of a vast fund of stories that testify to this…

There was once an English monk staying at Wat Pah Pong who had been teaching English in Thailand prior to ordaining. After having been in robes for some time he received a letter notifying him of the tax he owed on the money he had earned while teaching. Not knowing what to do he mentioned his situation to various people in the monastery and their reactions were as you might expect: they moaned and grumbled and fobbed the tax collectors off. Then he went to Ajahn Chah to see what he thought. I doubt the monk was expecting this classic response: “You must help them,” said Ajahn Chah. “They have a job to do. You must help them.”

So his loving-kindness was all-encompassing. But how often do we read about Ajahn Chah actually teaching us to develop it? I cannot think of many instances at all. What we do find him constantly teaching, however, is the need to cultivate wisdom. This is because loving-kindness depends on wisdom. Without wisdom there can be no real love. Our loving-kindness will only go as deep as our wisdom, no deeper. And what is wisdom? It is insight into the Noble Truth of Suffering.

Some people feel that the term suffering is a little strong as a definition of dukkha. It’s true, we may want to refrain from using it too much when we introduce Buddhism to newcomers. But when we really begin to look at life, when we really see what life actually is, then we find that suffering is a pretty accurate description! We are born, we age, we get sick and we die. We balance precariously on the crest of the wave of impermanence, where every experience rushes by never to be seen again. We cannot hold onto any possession or person no matter how dear, for they are also swept away by this inexorable law of change. And at any time our life or the life of one close to us can be lost in an instant. How often do we see in the news a story about a family who were on their way to the seaside but never arrived? Did they ever think that could happen to them? Do we think that could ever happen to us? On seeing how all beings are oppressed by this same suffering loving-kindness wells up in us and we cannot help but think “May all beings be happy and free from suffering!”

And because loving-kindness sees that we are all of the same kind: vulnerable beings caught in the whirlpool of ignorance, craving, hatred and suffering, it is unconditional. It does not pick and choose. It does not think ‘I will love this person but not that person’. Just as the sun shares its light and warmth with all beings irrespective of race, religion, sex, gender or class, so too loving-kindness shares its warmth and light with all.

Non-Attachment

Seeing that genuine loving-kindness arises from wisdom, it must therefore be free of attachment. Attachment is a bar to real love. Some people new to Buddhism jump up and down when they hear this. Not long after I went to the monastery a woman whom I had known previously came to meditate with her friend. During tea-time she asked Luangpor this question: “Isn’t it irresponsible to not be attached?” This old chestnut arises because of a lack of understanding of what we mean by non-attachment, as if it is cold, heartless and uncaring. I’ll give an example that involves my mother to show how this isn’t the case.

Naturally she had a hard time accepting my move to the monastery nine years ago. At one point she went as far as saying that I might as well have been dead! But gradually the tables turned and she began to venture here on the odd occasion when I was giving a talk. “Tell me when you’re on,” she’d say. I suspect her interest was not initially in the Dhamma: I don’t imagine she heard a word I said since she was too busy watching me! But her eyes soon closed and the teachings settled in. That, combined with the meditation, inevitably meant changes took place. Then, last November, while driving back from the airport after having said goodbye to my brother before he took off to find work in New Zealand, she was struck by one of those changes. “This is extraordinary,” she thought to herself. “I’m not upset.” She had intuitively grasped the pointlessness of holding on and not letting go. Consequently her attachment had been reduced, and with it her suffering.

Can we say this was an uncaring reaction? Can we say it was cold? Of course not, because it wasn’t. It was a wise and sensible reaction that benefitted both herself and her son. After she had told me this we discussed the nature of attachment and how unhelpful and selfish it is. It is founded on what I want, what I need, how I want to feel, what I want you to do. Attachment is a bar to real love because it centres on ‘me’ and ‘mine’. Loving-kindness in the ultimate sense is blissfully devoid of all notions of self and other.

Under All Circumstances

Are there any circumstances when loving-kindness is to be exchanged for anger and hate? No. The Buddha went as far as to say that even if bandits were to sever you limb from limb with a two handled saw you should maintain a mind of compassion, and that whoever gave rise to a mind of hate would not be following his teaching. This is obviously a tall order: most of us might be slightly put out if we found ourselves in that position! But at least we know where Buddhism stands in terms of retaliation, violence and, especially, WAR. At least we know where to aim in even the most difficult circumstances.

There is a powerful story of the Chinese Master Hsu Yun showing loving-kindness and compassion even in the face of the most brutal of attacks.

He was in his 113th year when his monastery was besieged by a gang of hooligans. Monks were beaten and even murdered as the monastery was raided for money and weapons that the assailants wrongly believed were stored there. The master himself was dragged into a small room and interrogated as to the whereabouts of the booty. Determined to extract a confession the thugs laid into him with their heavy boots and steel poles. As the blows rained down and the old master’s body crumpled to the floor he withdrew into a deep state of samadhi. Thinking the master was dead, the group departed. Immediately his attendants rushed in, and, detecting warmth in his cheeks, sat him up in the meditation posture. On returning the following day the thugs were furious to see him sitting up and so once again the master was pummeled into the ground. When they came on the third day and found him again sitting in meditation they became frightened and ran away. A week or so after that first attack, while patiently watching for a change in the master’s state, his attendants heard a groan. He had emerged from samadhi, only to become painfully conscious of his bruised and swollen body. Later on he was asked why he had come back, why he had not just renounced his life and attained Final Nibbana. His motives were born of loving-kindness and compassion: he couldn’t allow himself to die for it is a terrible karma to kill an enlightened being.

WAR

And WAR. Does it really need to be said that Buddhism does not condone WAR? Apparently, yes. Okay, soooo…. the case for a just WAR. On your marks. Get set….

A Buddhist country is under attack.

The very existence of the beacon of wisdom and peace hangs by a thread.

Aware that Buddhism will be destroyed if they do not fight the persecutors, the Buddhists take up weapons.

The enemy is thus destroyed and Buddhism saved.

Or was it?

NO..Of course it wasn’t. It was destroyed along with the enemy.

To die with loving-kindness in mind is better than living with blood on your hands.

.

.